Vocab

Line Size

Tags

General

A structure to store frequently used data. Faster access time than memory, but less storage

Takes advantage of the locality principles:

- Spatial Locality: Values needed often grouped together

- Temporal Locality: The same values often needed more than once

They’ll have a replacement scheme:

- LRU

- MRU

- FIFO

- Random

- Etc.

Generally, a cache can be though of as a 2D array or matrix, but depending on the scheme will use different elements, or use them in different ways

- Line Size - These are how much storage space is allocated for each row of the cache. This is essentially how wide the data in a row is.

- With more nuance, its the amount of data in a row attributed to a tag. An address split TTEEOOO (for this example specifically XXXY Y010) means that it will bring in XXY Y000 through XXY Y111 because they are all associated with the same tag XX and entry YY.

- 8 bytes of line size means 8 different bytes of memory are brought in.

- This takes advantage of spatial locality, increasing the chance that subsequently needed data will be included in the cache, brought in as part of the block.

Cache Pollution - Bringing in a lot of storage that we are not going to use. No need to bring all of memory, tread the line between making sure necessary things are in the cache, and not polluting it by bringing in everything.

Cache Programming - Generally not done. By design, caches are built to be invisible to the programmer, facilitating things silently. On top of that, cache implementations, sizes, number of caches, etc. are not standard across machines, and are vary hardware specific. As such, most languages don’t offer direct ways to interact with cache allocations, as that would limit the portability of the program.

However, it’s a damned if you do and damned if you don’t, because you’re leaving performance on the table if you do not understand and exploit your cache. Potential optimizations are specifying what variables are to stay in cache for quick access, increasing/decreasing code blocks/loops to fit within cache sizes, etc.

A well designed cache will hopefully manage a lot of this for you.

Types of Caches

Direct Mapped Cache

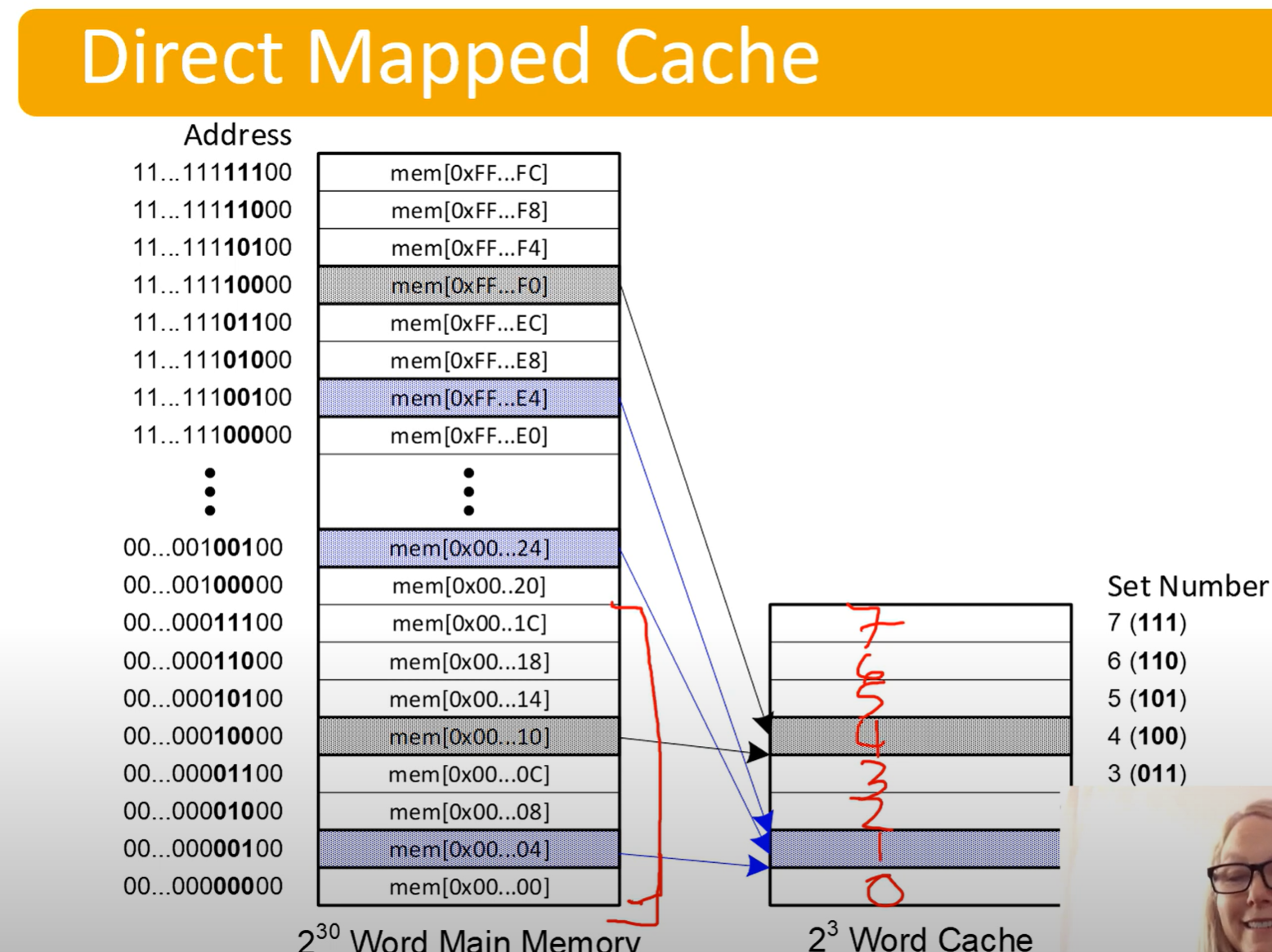

Direct Mapped Caches: Map a block of memory to one cache line

-

They do this be designating a certain portion of the address bits to be index bits, determining which line of the cache they get put in.

-

Notice the bits determining what line it gets put it

- It jumps by 4 because the last 2 bits would be offset bits, but are not being used for the diagram

-

Address bits will be split up as follows:

- Tag Bits | Entry Bits | Offset Bits

- Offset is the easiest to calculate: it log2(Line Size)

- Entry bits are the number of lines in the cache. This can be calculate by finding: cache size / line size. Then log2(num lines) gives number of entry bits

- log2(cache size / lines size)

- The rest are tag bits

Associative Cache

Associative Caches are named after associative arrays, where you search by value in parallel. Imagine searching a database by index, or using a hash map.

They use the addresses tag as the index/key, and map to the data.

- Address split up as follows

- Tag Bits | Offset Bits

- Offset calculated as usual, log2(line size)

- Tag Bits | Offset Bits

Set Associative Cache

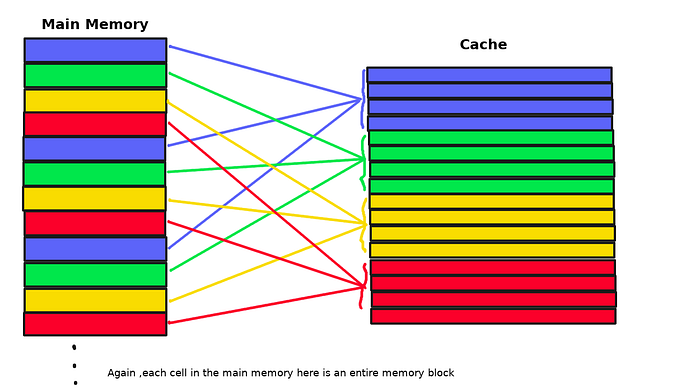

This is a hybrid approach, using multiple ‘small’ associative caches, and using index bits to determine which cache to map into

- Notice how they are not mapping to the same exact line as the direct mapped cache, but to the same ‘set’.

- In the name -way set associative cache, the # is describing how many lines are in a set, not have many sets there are.

Address bits are broken up as follows:

- Tag Bits | Set Index Bits | Offset Bits

- Offset calculated as usual, log2(line size)

- Set index is a bit more complex, number of sets can be calculated from the equation:

- set size = line size * how many lines in a set (the # associative)

- \# sets = cache size / set size