Prep

Information Representation

Computer Structure

Assembly

I/O

- I/O devices have IDs associated

- Dependent on I/O port

Two main Types:

- Dependent on I/O port

- I/O mapped I/O

- Memory mapped I/O

IO Mapped

- I/O devices and memory have separate address spaces

- I/O: 0, 1, 2, …

- Mem: 0, 1, 2, …

- Intel

- Memory: mov

- I/O: in for reading and out for writing

Cons:

- Need more buses because we need I/O bus and a memory bus

Memory Mapped I/O

- I/O devices and memory share the same adress space but we just reserve some of the address for I/O

- Ex (index is address):

[IO, IO, IO, Mem, Mem, Mem, ...]

- Ex (index is address):

- If intel used it:

- Both use mov, just for different addresses

Advantages:

- Both use mov, just for different addresses

- Get to treat IO devices like memory. No more instructions. C/C++ can access IO

Disadvantages: - Inacessible memory addresses

Instructions

Wait Loop IO AKA Polling:

- Repeatedly ask if it has input

- Once it has input, do something

Pros: - Simple

- Low latency: Gets addressed (read) quickly

- Can all be done in software

Cons: - Wasteful of CPU time

- Most of the time, no input

Interrupt Driven IO

- Get interrupted, then address the interruption

1. Running some program P

2. I/O device generates an interrupt

3. Save program’s state: EIP, EFLAGS, Seg

4. Ask the I/O device for its interrupt id INTA

a. Acknowledge interrupt

5. I/O device gives back its interrupt Id

6. Service the interrupt

7. Resume program P

a. IRET

Pros:

- Don’t waste CPU time

Cons: - Each instruction take slightly longer

- Higher latency

- More complex system

- Additional hardware

Interrupt Descriptor Table

- OS maintains a table of Interrupt Vectors

- Each vector stores the address of the ISR as well as some other information

- Protection levels - Entries are indexed by the interrupt ID of the devices

- Inside of the intel CPU there is another register called IDT that stores the beginning of the address of the interrupt descriptor table in memory

- OS filled in both the table as well as the register at boot time

Where is interrupt handled

- Interrupts checked for at the end of every instruction

- CPU Cycle: Fetch, decode, execute, write, check for interrupt, handle interrupt if there is one

Prioritizing interrupts

- Always serve the highest interrupt if multiple at same time

- During an interrupt could be another

- Always handle the new interrupt first

- Ignore interrupts until the current interrupt is finished

- Service the new interrupt but only if it has higher priority

OS

OS is a Program

- OS is a program

- OS is only special because it is the first program run

- For example, if there is a single CPU with a single core, you can’t run your own program and the OS at the same time

- Switch between programs with a system call

- Hardware can interrupt the program that is running

OS Handles:

- Managing the file system

- Manages memory

- Manages processes

- Manage I/O

Application Loading

-

Type ./a.out on the terminal -

Terminal will execute

execve("a.out")to tell the OS to start runninga.out -

Locate

a.outon the hard drive -

Read

a.out’s header. This has info abouta.outsuch as its size, where the text section is at, where the data section is at, where is_start, etc. -

Locate a free section of memory large enough to hold

a.outand copy it there- OS does all of the memory management so it knows which locations are free and which are in use. It “knows” this because it keeps track of memory tables that show which sections are in use and which are free

-

Save the operating system’s state (registers, permissions, etc)

-

Wipe the registers clean and set esp to the beginning of the program’s stack

-

jmptoa.out’s start -

a.outis now running

Booting the OS

- Bootloader is stored in ROM (read only memory) and ROM is nonvolatile. Resolves the chicken and egg problem.

- Intel when it turns on, EIP is set

0XFFFFFFF0, so this is where we place the bootloader - Bootloader reads the first sector of th disk and copies it into memory

- The OS saved itself to this first sector

- Jump to the location in memory we copied the first sector to and execute the instructions that are now there

- The OS then loads the rest of itself from the hard drive into memory

Time Sharing

- Time sharing is multiple processes taking turns so quickly that it appears that they are running simultaneously

- In time sharing processes are given a time slice aka a quantum to run

- There is a timer that goes off every X seconds. This timer goes off more frequently than a time slice. We might want the time slice to be Y seconds. So when the timer goes off goes

timer_count++, then whentimer_count==Y/Xthen switch to the next proces - Process is an instance of a program

Implementation

- Process X was currently running and its time is now over and we want to switch to Process Y

- Save X’s state in X’s entry in the OS’s process table

- Registers: all of them

- EIP, EFLAGS, and CS are on the stack at the moment. They are there because we got to this context switch handler via an interrupt and the interrup hardware in the CPU saces those values to the stack

- Load Y’s state from Y’s entry in the OS process table

- State == registers

- Also have to make sure Y’s EIP, EFLAGS, and CS are placed back on the stack

- Start Y

- Setting EIP back to the instruction that Y was on

- This is done via aniret

Run State vs Sleep State

- When a process is ready to be run it is run state

- When a process is not ready to be run it is in sleep state

- Generally a process enters sleep state when it is asking hte OS to do something on its behalf

- Get input, open a file, etc.

- Generally a process enters sleep state when it is asking hte OS to do something on its behalf

PraerieLearn

Interrupts:

- OS - IDT filled out

- OS - IDTR pointer to the beginning of the IDT

- Hardware - IO device asserts the interrupt line

- Hardware - CPU asserts the interrupt acknowledge line

- Hardware - IO device sends its interrup id back to the CPU

- Hardware - CPU saves flag register, PC, and the CS registers

- Hardware - CPU jumps to the appropriate interrupt handler

- OS - Interrupt actually serviced

CS Registers - Code Segments

- Base address of the segment where the executable code resides in memory

- Works with other registers like the IP

ISR - Interrup Service Routing

- Before using, save all registers (but ESP which you can use)

OS:

Program Running - EIP pointing to memroy belonging to your program

Program order:

./a.outtyped in shell- shell executes

execve - OS locates

a.outin the file system - OS reads

a.out’s header - OS searches memory allocations and tables for a space big enough. Copies a.out there. Updates its memory allocation tables and process tables.

- OS saves its state

- OS jumps to

a.out’s_start

If the OS is the program that loads other programs, how does the OS get loaded? How do we avoid the chicken and egg problem?

Make sure you reply to both questions explicitly. Consider using bullet points in your answer so that we know which parts of your answer correspond to which question.

- The bootloader is loaded in from ROM (read access memory). This is non volatile memory. The bootloader reads the first sector of the disk and copies it into memory, this sector holds to the OS. We execute the instructions now in memory, and from here the OS executes.

- This avoids the chicken and egg problem by having a non volatile process (the bootloader in ROM) explicitly designed to load the OS, and allow it from there to spawn new programs.

Timesharing depends on the following hardware components - the timer and interrupt

Chris Review

Integer Representation

Know:

-

Unsigned

-

Sign Magnitude (Same as unsigned with sign bit)

-

2s complement (The complicated negative one)

- Conversion:

- If positive, treat as unsigned. If negative, continue

- Flip all the bits and add one

- The number represented is the 2s complement negative representation

- Conversion:

-

Change of bases:

- Easiest way is to convert to ten as an intermediate step, then convert to the desired base

- Easiest way is to convert to ten as an intermediate step, then convert to the desired base

-

Hexadecimal

- Base 16, starts with

0x - Each number represents four bits

- Base 16, starts with

Floating Rep

- 1 bit for sign, 8 for exp, 23 for mantissa

1|10100100|10010010001011011010111- Implicit one in the mantissa

- The exponent has a bias of 127

- Essentially take away the leading bit, add one and that’s your exponent if positive

Array Representation

accessing: arr[a][b][c] with size (i,j,k)

Two Major Types, And in those types you have row/column major:

- One big chunk

- Row:

size = sizeof(pointer) + a(j+k) + b(k) + k - Column:

size = sizeof(pointer) + c(k+j) + b(j) + i *(arr + a(j+k) + b(k) + k)

- Row:

- Array of arrays

- Pointers to nested arrays:

*(*(*arr+a)+b)+c)

- Pointers to nested arrays:

Debugging

Assembly

In the x86 Assembly language, we have 6 general-purpose registers (EAX, EBX, ECX, EDX, ESI, EDI). We also have registers such as ESP (points to the top of the stack), EBP (bottom of a stack frame for a given function), and EIP (stores the instruction)

Assembly Boilerplate

.global _start

.equ ws, 4

# Locals

.data

a: .long 0

b: .long 0

c: .long 0

.text

_start:

done:

nop // newline after nop

Multidimensional Array Access:

movl arr, %edx

movl i, %ecx

movl (%edx, %ecx, 4), %edx # Accessing arr[i]

movl j, %ecx

movl (%edx, %ecx, 4), %edx # Accessing arr[i][j]

movl k, %ecx

movl (%edx, %ecx, 4), %edx # Accessing arr[i][j][k], final value stored in edx

Debugging

Compiling:

as --gstabs --32 -o hello.o hello.s

ld -melf_i386 -o hello.out hello.o

Printing:

p $eax # Registers have dolla

p (int)num # Need to cast labels

p ((int*)$eax)[0] # Need to cast eax value to int pointer, [0] dereferences the first element

p ((int*)$eax)[0]@10 # Starts at 0, prints 10 elements

C Callable Functions in Assembly

Function Calling

The caller will push args to the stack in reverse order (so the first arg is on top, f(a,b,c) => push c, b, a)

- It also pushes a return label/address to continue execution from

The callee then deals with the EBP, ESP, and maintaining registers

Prologue

Establish the stack frame for the current function

EBP holds the pointer to the start of the stack frame

Stack frame is everything between EBP and ESP

The stack frame gives you a fixed location for accessing locals and arguments

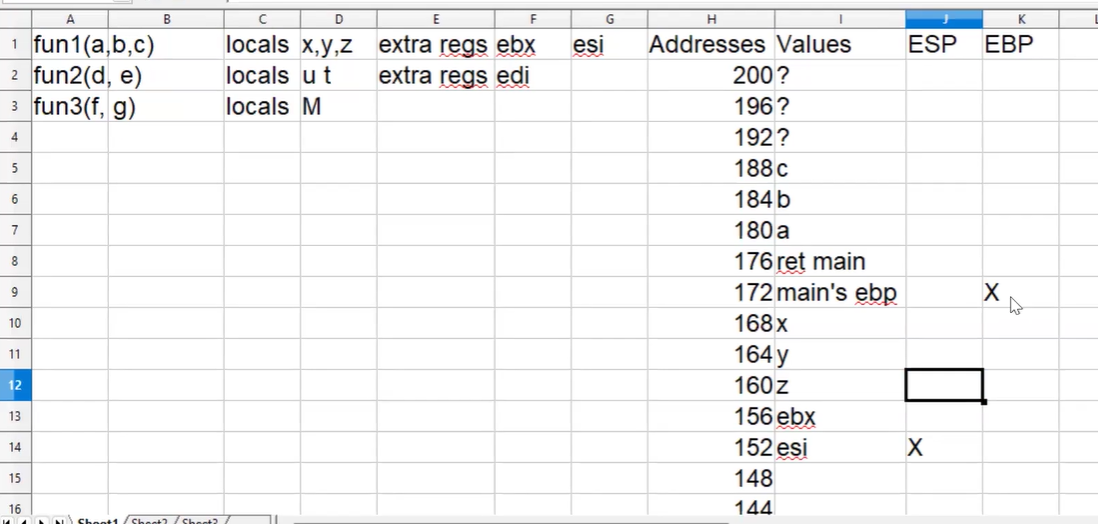

ESP keeps changing throughout the runtime of your function so it makes really hard to keep accessing locals and args through it because it keeps changingpush %ebp movl %esp, %ebp subl $num_locals * ws, %esp Push those registersEBP Offsets for args:

Positive offsets are function arguments

Negative offsets are local variablesAfter the prologue of fun1(a,b,c)

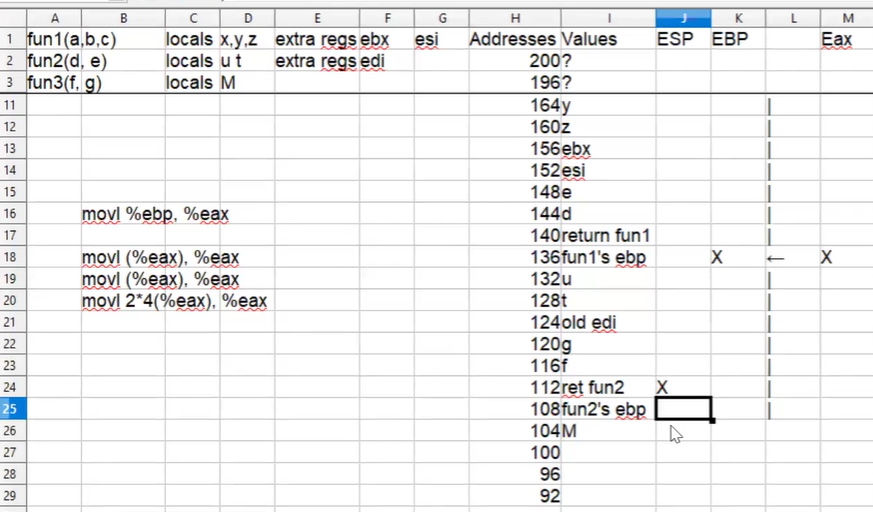

Can move up to a future by following the ebp pointers of call stack

movl %ebp, %eax // ebp into eax movl (%eax), %eax // following the ebp pointer (fun3->fun2) movl (%eax), %eax // following the ebp pointer (fun2->fun1) movl 2*ws(%eax), %eax // accessing the 1st fun1 arg, aEpilogue

Undoes the prologue

Restore saved registers

Remove the locals

Restore the old stack framePop the saved registers off the stack or move them off the stack movl %ebp, %esp pop %ebpAfter the epilogue of fun3(f,g)

Link to original

Using this, you can even call assembly functions by pushing args to stack, and using the return value in EAX

Inline Assembly

Boilerplate

__asm__(

/* Code */ :

/* Outputs */ :

/* Inputs */ :

/* Clobber */

);

Syntax explained in cheat sheet, have different types of outputs and places to store it:

- Writeable, early write, bijective

- Specific register, memory, general register, compilers choice